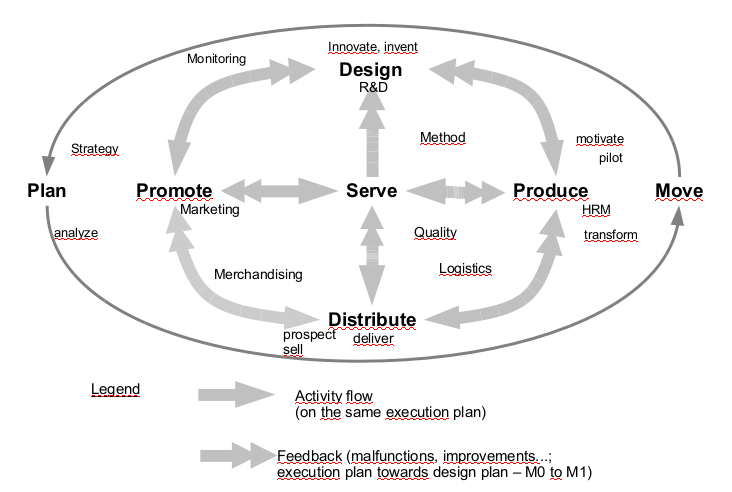

This “TransOp” diagram superimposes three structures to deal with a critical subject: the continuum between operations and transformation. The agile enterprise must seek better integration between everyday activities (the operations) and transformation activities, which are seen to be more exceptional.

This schema brings several traditions together:

- that of quality, with the Deming wheel (or PDCA for Plan-Do-Check-Act);

- that of methodology, with the opposition analysis-design completed by execution;

- the current discourse on transformation.

The continuum between operations and transformation

Seeking agility

The classic analysis-design dichotomy alone is not enough to cover the whole transformation chain and provide an account of enterprise life. It emphasizes study activities to the detriment of everyday activities. We therefore have to complete it with a third type of activity: execution, which is far more important in terms of volume. This is all the more necessary, as we now have to think about a closer linkage between operations and transformation, so as to increase enterprise agility, that is to say its capacity to rapidly adapt itself.

Put in place the improvement loop

This tripartition of Analysis-Design-Execution enables us to cover the complete scope, which can also be analyzed using the Deming wheel (PDCA). This schema allows us to draw a parallel with the quality approach.

The analysis encroaches on the “check” part. This means that there are two levels of verification or, more likely, two levels for the observation results to be taken into account:

- one, common, with the decision made by the producers (or the ones who execute);

- the other, more exceptional, which lies within the improvement loop for practices.

Mobilizing all the actors with a view to continuous improvement

On a larger scale and to clarify the roles involved in the transformation, we can position the separation between the transformation activities and the execution ones (the operations) on these templates. The transformation begins with a particular level of analysis: the “meta” analysis – if we can call it that – which exploits internal and external observations, takes a step back from the existing practices and raises questions about the running of the enterprise. This data is then used in the design phase, which consists in imagining new ways of working.

The diagram shows that operational managers have to understand the broader scope of their role: not only are they responsible for the day-to-day operations, as designed and stipulated (the execution, including verification), but they must also consider things in such a way that makes them actors in the transformation.

This philosophy can be summed up in one watchword: “We are all actors of the transformation!”

For further details:

- The Enterprise Transformation Manifesto.

- The exceptional training course “Business Architecture & Transformation”.